Genny Lutzel, Family Member

Genny Lutzel is the daughter of a resident in an assisted living facility in Dallas, Texas. She has been caring for her mom who has been living with advanced Alzheimer’s for close to nine years. Click the black squares ![]() below to hear and read about Genny’s experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. The expanded interview (edited for clarity) is available at the bottom of the page.

below to hear and read about Genny’s experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. The expanded interview (edited for clarity) is available at the bottom of the page.

And I played keyboard for her to sort of generate that memory of her past music life. And we might come here to paint nails, put makeup on…those are the kind of activities, that one-on-one. So staff is doing more custodial care — she cannot participate in bingo or a group activity. She might sit and listen to music, but she is in that stage where one-on-one, that eye contact…she may not know me but I know her well enough to connect to her. And that was gone.

The only thing we did to persons in long-term care during visitation restrictions was isolate them. That was the only thing we did and that caused more harm and more devastation than can be ever recovered for a person living in long term care, especially an elderly person.

Everything about her gives me a clue on what’s going on with her that’s completely nonverbal. So last year in May when I was told I could no longer see her, my utter terror began because I could no longer see her eyes in person, see what was going on with her body, or just be in the same room with her to make those determinations.

My mom did contract COVID it was brought in by a staff member. In this particular case, a staff member kept coming to work with COVID and did not look at her email to know she was positive. So by the time she did, we were all exposed.

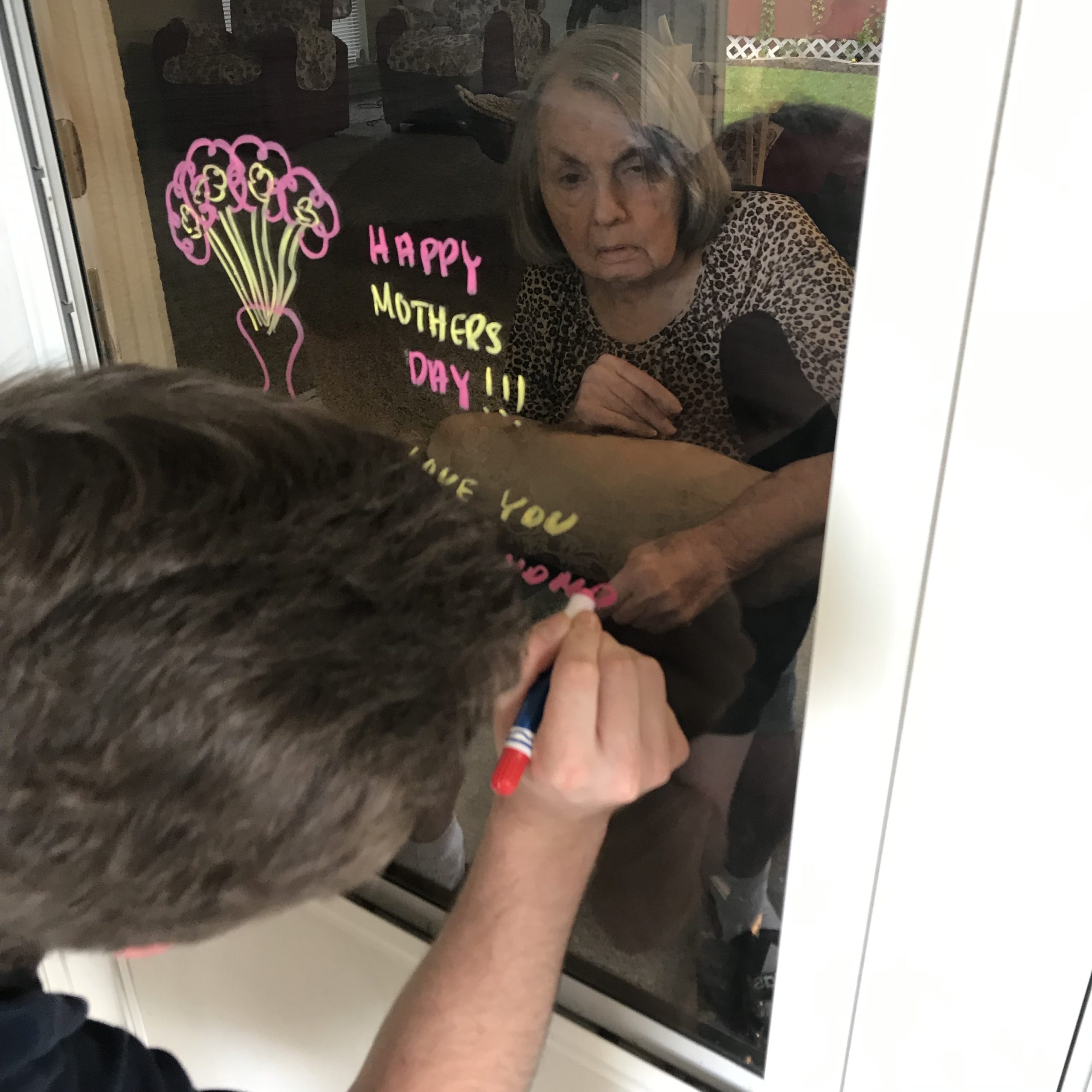

She lifted up her hand to the door handle as if to tell me, “Look Genny, this is how you get in my door. You just put your hand up here on this door to open it.” I felt that she was trying to communicate. She couldn’t understand why I’m out there. The door handle is right there. So that was one of those moments where I thought, I can tell her white lies or I can just tell her, “Mom I can’t come in until it’s safe.” And so each time I did that it was an affirmation for me of why I couldn’t go in. It was a way for me to hold back my tears for not being able to go in and to tell her in a believable way “it’s okay, this is okay, this is how we’re going to do this for a while.” And then I would leave and cry [laughs] in my car on my own, never in front of her. I didn’t want her to see that something was wrong with the way we were visiting.

So I will ask her, “So, Mom do you want to listen to some polka music today?” And she will nod her head yes, and on it goes on the device. So whether or not she can communicate in a way like we are doing right now, she can understand basic thoughts that I am conveying to her and respond appropriately but as a head nod or a head…you know, either way it’s a head nod. She will hold on to my hand when she thinks it’s time for me to go, and just grip that a little bit tighter when she anticipates it’s time for me to leave. When I ask her to wave goodbye when I’m leaving her room, it is the just most tender moment. Because as frail she is, she still understands the way it looks if her hand is resting, it looks like this. That’s her way; she’s making the motion, she’s making that connection so all of those things are her means of communicating.

Click below for the expanded interview (17:00).